Orioles are especially impressive songbirds, found throughout much of the temperate and tropical regions of the Americas, numbering 32 species in the genus Icterus. Of this diversity of beautiful songbirds, from May to August or early September I thoroughly enjoy 2 species at my feeding station, in my yard and neighborhood, and in the surrounding region – Baltimore and Orchard Orioles. The larger male Baltimores provide remarkably deep orange and black colors and beautiful songs and the females are less distinct in their varied plumages.

Orchard Orioles are the smallest of the orioles that range as far north as the United States and Canada, and they have 3 very obvious plumages that distinguish adult males, adult females, and yearling males (also referred to as second year males). The adult males and females are very distinctly colored and both are exceptionally beautiful. Usually, yearling males are rarer among migrating and nesting populations, and they have some color qualities of both the female and male. They are similar in color to females with olive backs and yellow ventral sides and heads, but they have a distinctive black facial mask that makes them quite unique.

I can’t say why, but yearling male Orchard Orioles have always caught my attention, and it’s always been especially interesting when one or more came into view outside my office windows. It seems that year by year, sightings of yearling males have become more frequent, and this spring they have been most common of all, with at least 5 yearlings males visiting my grape jelly feeders – with 3 arriving at the same time once last week.

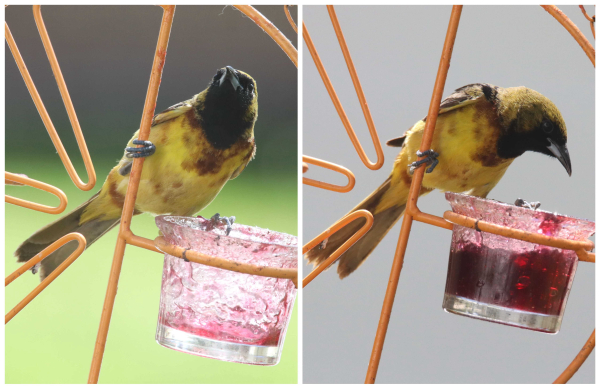

About that time, I began to notice 2 yearling male Orchards that appeared to be beginning to molt from their yearling plumage to an adult male plumage. They showed more black feathers beyond the usual black mask, with individual black feathers extending to their nape and onto their upper back. Even more interesting were chestnut-colored feathers close to the black mask plumage, and one of the yearling males had fairly extensive chestnut-brown plumage on its breast, surrounding its vent, and scattered across its yellow belly plumage. It had the overall appearance of being in the midst of a molt from its yearling plumage to adult male plumage.

Documentary Photos

That’s when bird photography came into play. I like to photograph different orioles that visit my feeders to document different plumage variations and try to keep track of individuals. Now I had another angle – to document a stage of an Orchard Oriole molt, including the sequence of feather replacement from a yearling male to an adult-plumaged male. Actually, my “circus feeder” is perfect for getting some interesting documentary photos, first because the orioles prefer feeding from it, and ultimately because they perch in a variety of positions that show their anterior and ventral sides, as well as their right and left sides.

Even though the orioles are close enough to see features with the unaided eye, binocular views are tremendously better, as are zoomed-in camera views. But there just isn’t anything to compare with a digital photograph to enlarge and have a chance to really study feather to feather variations in a bird’s plumage. That’s when I could see plainly that there were more black feathers along the upper back of the more advanced yearling male, including some wing feathers, and that its 2 central tail feathers had been replaced with black tail feathers (rectrices).

An adult male’s plumage is colored dramatically different from the yearling male in the top photo, and here you can see how the molting male will look when its molt is complete (500mm zoom lens, f-6 aperture, 1/3200 shutter speed, 800 ISO).

|

I share this information and photo illustrations of my “photo study” to show yet another way for us to use our camera to photograph birds, to document different plumages that distinguish different sexes and ages of birds, and to appreciate what we can learn more about birds right outside our home or office windows. Then too, these birds can get your creative juices flowing and inspire you to learn more about a given species. Certainly, the yearling male Orchard Orioles did that for me, and it has made me a better birder who can share my photos and impart some interesting information about birds when they come up in conversations. And it was great fun to break up periods of office work – ain’t birds wunnerful!

Article and Photographs by Paul Konrad

Share your bird photos and birding experiences at editorstbw2@gmail.com